- Divergent Creativity Techniques: How to Generate Non-Standard Ideas

- Freewriting — Subconscious Creative Technique

- Dream Journaling as a Technique for Finding Creative Solutions

- Free Association: A Creative Thinking Technique

- Wishful Thinking — Creativity Technique for Breakthrough Innovation

- “What if?” — A Powerful Creativity and Possibility Thinking Technique

- Role Playing as a Creative Problem Solving Technique

- Metaphor technique for Creative Problem Solving

- Reversal (Inversion) as a Creative Problem Solving Technique

Divergent Creativity Techniques and

Their Practical Value

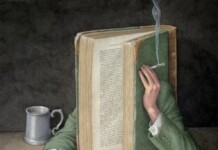

Divergent Creativity Methods are open, intuitive, and exploratory techniques designed to generate the widest possible spectrum of ideas, solutions, and problem approaches. They stimulate free divergent, lateral, and possibility-oriented thinking and encourage unexpected associations, often engaging subconscious processes and hidden imaginative resources.

The central principle of these techniques lies in producing an unrestricted flow of ideas while deliberately suspending criticism, conventional patterns, and limiting assumptions. They reduce internal control, foster non-standard perspectives, and create conditions for transcending habitual experience. In this way, they expand cognitive boundaries, activate right-hemisphere and associative thinking, and encourage bold and non-obvious solutions.

Divergent Techniques are particularly effective during the early phases of the creative process, such as problem discovery, hypothesis formation, and initial idea generation, where the exploration of possibilities takes precedence over immediate solutions. Unlike convergent Techniques, which emphasize rationality and efficiency, divergent approaches prioritize fluency, originality, and imaginative potential, often postponing concerns of applicability.

Main Characteristics of Divergent Creativity Techniques

1. Freedom and openness: absence of strict rules and constraints, encouragement of spontaneity.

2. Intuition, imagery, and subconscious use: orientation to unconscious processes, intuition, associative links, reliance on metaphors, symbols, dreams, and role-play transformations.

3. Associativity and lateral thinking: use of unexpected connections, random stimuli, inversions, and perspective shifts to go beyond patterns.

4. Exploratory approach: encouragement of experiments, “what if” thinking, use of unusual perspectives and scenarios, temporary suspension of all constraints, including fundamental laws of reality.

5. Flexibility: applicability for both individual and group work, from personal practices like freewriting and dream journaling to group brainstorming sessions.

Advantages and Practical Value

The main advantage of divergent techniques is overcoming psychological barriers and stereotypes of thinking. Divergent Techniques are especially valuable in situations requiring novelty and non-standard solutions. They are indispensable in cases of creative crisis or when dealing with complex, overused, and stereotypical problems.

They expand the search space, increase the scope of possibilities, and provide access to hidden, fleeting but valuable ideas. At the same time, they create an atmosphere of openness and trust, a psychologically safe environment for expressing any ideas, which is particularly important for team building.

Their practical significance manifests in generating ideas for business innovation, design, advertising, art, and scientific research. They also show high effectiveness in education, creativity development, problem-solving, personal creativity, and self-development.

At the same time, it must be remembered that the productivity and effectiveness of divergent techniques depend on their correct and skilful application. Possible difficulties include idea overload, blurred results, and risk of superficiality. Unstructured processes are energy-intensive, may cause fatigue, and therefore require clear time management. Moreover, divergent techniques rarely produce ready-made solutions—their main value lies in creating raw material for subsequent analysis and refinement by convergent techniques.

Recommendations for Optimizing Divergent Techniques

1. Clearly define the goal and formulate the problem. Before applying the technique, clarify the specific task (e.g., idea generation, overcoming a creative block) and formulate the key problem or guiding question.

2. Create a safe environment and a creative atmosphere. Participants must feel comfortable proposing any ideas, including wild or unconventional ones. Establish strict ground rules: “no criticism” and “yes—to strange ideas.” A sense of total freedom to propose even eccentric suggestions is crucial.

3. Use rhythm and timing. Time limits stimulate spontaneity, sharpen focus, and reduce self-censorship. Set time boundaries (e.g., 10 minutes for freewriting). Work in intervals of 7–12 minutes with short breaks; 3–5 cycles are more effective than one long session.

4. Apply the principle “quality through quantity.” Set ambitious quantitative goals: for example, 50 ideas in 15 minutes or 3 unusual associations between distant domains. Introduce “forced constraints”: one idea in 30 seconds, using only verbs or metaphors, or solving the problem “as if you were an alien.”

5. Capture absolutely all options without exception. Record every idea in 3–7 words, without editing during generation. Use color-coding for different Techniques or participants, create mind maps, and mark ideas worth revisiting with a special symbol. Employ idea counters or visual boards to track outputs.

6. Combine Techniques. Begin with a “warm-up” such as 2 minutes of free associations. A productive sequence includes: generation (Brainstorming, Random Word, What If?), transformation (Inversion, Metaphors), and perspective-shifting (Six Thinking Hats, Imaginary Characters). Prepare a “stimulus bank” in advance—lists of random words, images, roles, and domains to spark unexpected connections across distant fields.

7. Always transition to convergence. Divergent thinking is meaningless without subsequent analysis, filtering, evaluation, and concretization of the most promising ideas. These are two phases of a single process. The core rule: maintain high divergence at the entry point, process discipline in the middle, and rigorous convergence at the output.

8. Manage team dynamics. In group work, balance individual and collective cycles: 5–7 minutes of individual ideation followed by 10 minutes of group sharing and discussion.

9. Leverage digital tools for generation, capture, and structuring. Use Miro for visual brainstorming, Evernote for freewriting, and specialized applications for idea clustering and structuring.

10. Continuous improvement and retrospective analysis. Implement the practice of systematically reviewing creative sessions. After each intensive interval—or at the session’s close—set aside 5–7 minutes for a structured retrospective. Key reflection questions include: What enhanced idea flow? What hindered it? Which stimuli worked best? Maintain a “registry of effective techniques” to capture and reuse successful practices.

Strategy for Selecting and Combining Techniques

1. Vague problem (finding ideas, topics, direction): Freewriting, Dream journal, Metaphors.

2. Breaking patterns (overcoming a block, searching for innovations): Random word, Inversion, Bisociation.

3. Perspective shift (deep problem work, risk assessment, empathy): Imaginary characters, “What if?,” Wishful thinking.

Strongly Divergent Techniques

Open, intuitive, exploratory

These Techniques emphasize freedom, intuition, and minimal structuring, encouraging the unrestricted generation of ideas. Priority is given to the most divergent techniques—those characterized by free idea flow and the absence of strict frameworks.

1. Freewriting (Peter Elbow, 1973). A technique of continuous writing over a fixed period without stopping, editing, or censoring. It bypasses the internal critic and provides access to subconscious ideas.

2. Dream Journal (Carl Jung, 1920s; Patricia L. Garfield, 1974, 1995). The systematic recording and analysis of dreams to extract symbolic imagery and unconscious solutions to creative problems by engaging with the unconscious.

3. Random Word Technique (Edward de Bono, 1968). A lateral thinking technique that uses an arbitrarily chosen word as a stimulus for generating new ideas through unexpected associative connections.

4. “What if?” Technique. A Technique of exploring alternative scenarios by posing hypothetical questions, expanding the boundaries of possible thinking.

5. Wishful Thinking (Arthur VanGundy, 1988). A creativity technique based on articulating ideal desired outcomes without regard for current constraints, followed by searching for pathways to achieve them.

6. Imaginary Characters Technique (Role Playing) (Sidney Parnes, 1967; Rick Griggs, 1967; Michael Michalko, 1991). A problem-solving approach that involves adopting the roles of fictional or symbolic characters, enabling the exploration of a problem from multiple unusual perspectives.

7. Classical Brainstorming (Alex Osborn, 1939; 1953). A group creativity technique designed to generate a large number of ideas by encouraging unrestricted participation and postponing judgment.

All types of Brainstorming

8. Association Technique. A technique that generates ideas through chains of related concepts and images, leveraging the brain’s natural capacity for associative thinking.

9. Garlands of Associations (Genrikh Busch, 1976). An advanced associative technique that creates branching networks of interconnected concepts for a comprehensive exploration of a theme.

10. Bisociation Technique (Arthur Koestler, 1964). A creative thinking technique based on the intersection of two unrelated thought systems or knowledge domains, producing unexpected insights.

11. Metaphor as a Tool for Creative Problem Solving (used since antiquity; systematized by William J. J. Gordon in the 1960s; Stanley Raffel, 2013). A technique of transferring properties and relationships from one domain to another through figurative comparison, facilitating the understanding of complex concepts.

12. Inversion or Reversal Technique (Charles Thompson; Edward de Bono, 1970s). A technique of exploring solutions by considering the opposite approach to a problem, often leading to surprising and effective results.

Thus, divergent creativity techniques are essential tools for expanding the boundaries of thought.

When effectively combined with convergent, analytical approaches, they form a balanced and powerful toolkit for breakthrough innovation. This makes them especially valuable and useful for practitioners across diverse fields.